- Home

- Detection Club

Ask a Policeman Page 8

Ask a Policeman Read online

Page 8

“Yours ever,

“MILWARD KENNEDY.”

“P.S.—I find that I have made an awkward blunder. By a clerical error I have mixed up the sleuths. I have asked Dorothy L. Sayers for Mr. Sheringham’s views, Anthony Berkeley for Lord Peter’s; I have applied to Helen Simpson for Mrs. Bradley’s aid, and to Gladys Mitchell for Sir John’s. Never mind; let us see what happens.”

PART II

CHAPTER I

MRS. BRADLEY’S DILEMMA

BY HELEN SIMPSON

(I)

MRS. BRADLEY was the perfect guest. Even relatives-in-law, those touchy, difficult, and chary hosts, continually requested her to stay, were disappointed when she refused, and frolicked about her like puppies unleashed when she spared them a week in the summer. This similitude might hardly apply to the stately gambols of Lady Selina Lestrange, who weighed fifteen stone, and seldom moved far save under haulage; but the moral effect of Mrs. Bradley’s visits may be thus, not inadequately, represented. The lure on the present occasion had been horticultural and psychological.

“Really, Adela dear, I want to consult you about Sally. She seems to be growing quite morbid, won’t go about, meets a most impossible person secretly, and has been getting, I find, all sorts of dreadful medical books from the London Library. I wrote to them and stopped it, of course. She is behaving very badly to that nice Dick Paradine, you knew his father, and of course I have no influence, but I believe the child really respects your opinion. Our borders are exquisite, it seems hard to realize that with all this taxation we may have to cut down the outdoors staff, and next year it will be a wilderness. So do come—”

Thus Lady Selina, at her none too extensive wits’ end; to which Mrs. Bradley crisply replied:

“I should like to see your garden, and will come, if I may, next Monday. Sally, I imagine, needs something to do rather than someone to marry.”

The result of this interchange was Mrs. Bradley’s arrival in time to drink tea under an immemorial elm on the Lestrange’s lawn, and, with a bright, black eye alert for wasps, to listen to her sister-in-law’s moan.

“—and she won’t be civil, except to this awful young man, and she huddles herself up all day in her room. It’s morbid, and if there’s anything I dread—it’s bad enough having Ferdinand always in the papers.”

“To say nothing of me,” supplemented Mrs. Bradley with a gleam.

“Darling, I know you never actually seek notoriety. But I mean, all this obsession with crime! I do think Ferdinand might sometimes find someone respectable to defend.”

That famous criminal lawyer’s mother gave a loud cackle of laughter that set off Lady Selina’s parrot, who had been brought out for an airing in the June sun.

“Ha, ha, ha,” observed the parrot shrilly. “Give us a kiss, give us a drop o’ beer. Smack!”

To this Mrs. Bradley’s cackle played second, and the duet brought a figure to one of the second floor windows of the distant house. Mrs. Bradley’s sharp eyes noted it at once; noted, too, an odd appearance about the mouth, as of a thin dark moustache. “Pencil,” proclaimed her thoughts, while her remarkable voice responded in the negative to her hostess’s question concerning more tea.

“Delicious, but no more. Your garden’s divine. I simply ‘must walk about.”

“Shall I come with you?” Lady Selina’s fond gaze was on the strawberries, of which she had already consumed two platefuls.

“Stay where you are,” commanded Mrs. Bradley. “Goodness, I’ve known you more than seven years.”

“I thought that was poking fires.”

“Gardens too,” responded Mrs. Bradley firmly, who detested a personally-conducted tour as intensely as she favoured a solitary stroll. Her objection was sustained by the parrot, who exclaimed with hospitable heartiness:

“Give ’er air, give us a drop o’ beer, hullo, hullo, she’s my sweetie!”

Mrs. Bradley thus encouraged set off on her tour, keeping well within the field of vision of the second floor window, slowly ranging, surveying flowers with almost professional deliberation. She had worked round to that side of the garden where rhododendrons, past their prime but still heavy with bloom, made an impermeable screen, when she heard the expected voice.

“What are you doing, Aunt Adela, snooping about?”

“I am snooping, Sally, if that nondescript word means exploring, your mother’s garden.” She eyed swiftly, piercingly, the slim young figure before her. “And what about you?”

“Mummy’s asked you to talk to me, hasn’t she?” asked Sally with no preliminary sparring.

“She did,” admitted Mrs. Bradley, unconcerned, “but I shan’t need to.”

“Oh!” Sally was momentarily dashed.

“When,” pursued Mrs. Bradley, “I hear of a girl who shuts herself up in her room, and gets in medical books, and snubs her admirer, I don’t jump to the concluson that she’s going to murder him. I assume at once that she is writing a detective novel.”

Sarah stared a moment, and gave vent to an expletive which wrinkled Mrs. Bradley’s eyes with distaste.

“Blast! And I didn’t want Mummy to know!”

“So you shut yourself up, and don’t go out, and won’t be civil, and generally behave in a way calculated to drive her to frenzy.”

“Don’t go out! Where is there to go? You don’t know how dull it is here.”

“Dull, with his lordship of Common-Stock at your back door?”

“He’s an old toad. He’s vile to everybody. Teddy Mills told me—”

She halted. “Oh, well, I don’t suppose it matters. Teddy’s leaving the old brute, anyway. But he said sometimes he feels like strangling him. He uses money like a bludgeon, and publicity like poison-gas.”

“A quotation from your book, I presume,” said Mrs. Bradley, “or from Mr. Edward Mills?”

“As a matter of fact,” Sally answered, with an innocent air, “I thought it would be rather fun to make my murderer someone like Lord Comstock.”

“Never embark on a jargon you don’t know. Landed gentry are more in your line, and journalese is one of the more difficult languages.”

“Oh, Teddy helps with that.”

“H’m!” Mrs. Bradley cleared her throat with emphasis, and lifted one yellowish claw covered with admirable but equally yellowish diamonds. “Edward is forbidden fruit; Edward takes your fancy. Edward’s employer is unsympathetic. Your mother also is unsympathetic. Don’t interrupt me. Comstock keeps Edward’s nose to the grindstone and makes his life a burden generally. It is difficult for you to meet Edward often; whose fault? The employer’s, naturally. You therefore start a novel, in which you avenge yourself on the employer by proxy, and with impunity. The name for this process is wish-fulfilment. Two centuries back people stuck pins into wax figures with the same idea.”

Sally, who had begun by looking angry, now had subsided to something like reluctant awe.

“I say, Aunt Adela, that’s most awfully good. Grand sleuthing—”

“Is it correct?”

“Pretty well. I mean, Teddy’s fearfully good-looking, and good at things, and that old animal won’t ever let him off the chain. And then Mummy’s always ramming Dickie-Paradine down my throat.”

“Do you want me to speak to your mother about it?”

“Oh no, please,” said the girl in a great hurry. “You see, there wouldn’t be much money, and of course he’s frightfully young and so am I really, if you come to think of it.”

Mrs. Bradley came to think of Sally’s seventeen years, and found them surprising in combination with this very reasonable attitude.

“The question of marriage hasn’t arisen, then?”

“No. Why should it? Why should one start off being all stuffy? Marriage is like cold cocoa, nourishing but nauseous.”

Mrs. Bradley surrounded this last remark with quotation marks, labelled it “Edward Mills, Esq.,” and passed on.

“I think I shall have to meet this young man.”

“I see. Ambitious?”

“Oh yes, fearfully.”

“Yet he is leaving this employment where he meets such daily stepping-stones to ambition?”

The girl flushed.

“Teddys awfully sensitive. Why should he stay and be treated like a pickpocket? Aunt Adela, swear you won’t say a word to Mummy about all this?”

“I’m your mother’s friend, you know,” Mrs. Bradley reminded her.

“Yes, but you didn’t play fair. I mean, you got it out of me—I mean, it’s Teddy’s secret as well as mine. And after all”—a touch, could it be of relief?—“he’ll be going away soon.”

“We’ll see,” said Mrs. Bradley. Then, briskly, “Let me help you with the book, at any rate. How far have you got?”

“Only the first two chapters.”

“Body on the floor, I suppose, in the study?”

“Yes. Shot. Lots of blood,” Sally responded with relish.

“Off with his head! So much for Comstock,” proclaimed Mrs. Bradley grandly, her amazing voice lighting up even so uninspired, so very blank a verse, into poetry. Another voice, an excited and bubbling voice, but one that knew its place, said at her shoulder:

“For you, madam. A note. Gentleman’s waiting.”

Mrs. Bradley was too much of her generation to give any outward sign of irritation or dismay. She did say, however, plaintively:

“Now, who can have found me here? “as she opened the envelope. The note was long; it covered two sheets, and when she had read it she paused a moment, weighing it in her hand with pursed lips, thinking. At last she asked of the waiting butler an unexpected question.

“What’s the time?”

It was six; five o’clock by what the agricultural neighbourhood called God’s time, and completely light. Her next question was to Sarah.

“Dear child, do you think your mother’s ban on young men would extend to an Assistant Commissioner of Police?”

And she handed the note, which Sarah conned.

“Heard in the village you’d just arrived. Look here, may I see you? Sorry, but it’s something really urgent, and I’ve got to get back to London at once. Please. A. L.”

“Now what,” pondered Mrs. Bradley, “can Alan Littleton’s really urgent trouble be?”

It was a rhetorical question, one, that is, which anticipates no answer; but answered it was, and from an unexpected source.

“Pardon me, madam,” said the voice of the salver-bearer, tremulous with that sweetest, supremest human joy, the joy of being first with the news. “Can the gentleman be referring to the murder of Lord Comstock?” And, while they gaped: “Found in his study, miss. Shot through the ’ead. (Just ‘ad the news from the grocer’s boy, madam.) Shot right through the ’ead; blood”—the gleam in the salver-bearer’s eye betrayed him an amateur of crime—” blood everywhere.”

(II)

The situation was more than usually unfair to Lady Selina. Seated in a pleasant torpor, comfortably involved in a patent garden chair from which no unaided exit was possible, her contented gaze resting upon an empty cream-jug, she was suddenly assailed by her daughter, breaking the news that an Assistant Commissioner of Police was on the premises, and that her neighbour, whom she ignored while detesting, had been murdered during the day. At first her reaction to the double news was slow; the effect of the latter part, not unpleasant, being cancelled out by the former statement, which seemed to have more than a savour of the dreaded morbidity. But that savour, like a clove of garlic artfully used in cookery, rose gradually to appal and permeate her whole mind. That the neighbour should meet a thoroughly deserved end was nothing much; that her roof should harbour policemen was serious and unsettling, and a matter that must at once be dealt with in person.

Her first recorded utterance was: “Bother Adela!”

Her second: “Well, I suppose—but I cannot and will not have him to sleep!”

Her daughter, wrought to politeness and tact by this new excitement, reassured her.

“He only wants to talk with Aunt Adela. And he says he’s probably not a policeman any more.”

“Then why does he come here?”

“Aunt Adela, Mummy, I told you. He’s come about the murder. It’s frightfully important. Oh, Mummy, don’t go all Cadogan!”

Thus Sally who, with tact, but at a great expenditure of self-restraint, kept apart herself, and fended off her indignant mother from the concentrated talk which was proceeding in the breakfast-room, and whose progress, through the windows, she could witness; an impressive sight. Aunt Adela, shockingly and expensively dressed in her orange satin coat and skirt, sat bolt upright like a Buddha, only her quick black eyes moving. A dark lean man with a moustache gesticulated, standing. As she watched she saw him sketch a gesture, a very characteristic gesture, a sudden tugging at the lobe of the left ear by the right hand. He laughed as he did it. Sally did not laugh. For that was the way Teddy pulled his ear, and the very thought of Teddy, so sensitive, involved in this mess, turned her for a moment still as stone. When Alan Littleton came out to his car she was waiting by it.

“I meant to ask you—do you think I could have a word with Mr. Mills?”

Littleton looked at her.

“He’s at Winborough.”

“Winborough? Why?”

“He’s been—” he softened it—” asked to make a statement, I believe. But I can’t give you any exact information. I’m here as a private individual, you know. Must be off up to London again at once.”

“But what can Teddy know about it?”

“The police have to question everyone. It doesn’t mean they think he’s done it. I’m sorry, I must be off now.”

She watched the neat blue car with the recent dent in its mudguard disappear, spurting gravel as it went, and admired the Commissioner’s handling, for the drive was tricky. As an individual, however, she had less admiration for Major Alan Littleton. He had been abrupt with her. He had mimicked Teddy and laughed. He had a dark lean kind of good looks for which the rather ambrosial head and well-covered person of the late Lord Comstock’s secretary had given her a distaste. She wandered back into the hall, pondering. “Asked to make a statement.” What did that mean? Encountering Aunt Adela she referred the question to her.

“Probably,” responded that lady, “that they’re holding him on some sort of suspicion.” The girl flinched. “My dear child, what else could you expect of local police? Or Cabinet Ministers either; imbecility unfortunately isn’t confined to one class. They’ve suspended Alan, for instance, just because he happened to be there. And they’re asking all the wrong questions, of all the wrong people. This isn’t a crime that can be solved by measuring burnt matches and watching the clock. It isn’t a premeditated crime at all. Therefore”—Mrs. Bradley suddenly knuckled her niece jocosely in the ribs—” therefore it wasn’t Teddy, so try and look a little more cheerful.”

“Of course it wasn’t Teddy,” said the girl resentfully; and then, instinct demanding a backing of reason; “Why wasn’t it?”

“Girl! And you aspire to write stories about this sort of thing! A house full of respectable, right honourable and right reverend people, to say nothing of others we know nothing about as yet, but who may be presumed to come within one or other of those categories; the cook, the gardener, the unknown lady in Sir Charles’ car—you haven’t heard about that, of course; a house where policemen go casually bicycling by; a house swarming with visitors. And the confidential secretary, with all the twenty-four hours of the day to do his murder, chooses just that one, with eminent men popping in and out like cuckoos from clocks. Nonsense! The whole thing was a psychological explosion; the pistol, so to speak, was merely a symbol, merely the physical expression of a mental state. Whose? Well, we shall have to ask a few questions ourselves.”

&n

bsp; (III)

Mrs. Bradley began inquiries that night at dinner. It was easy enough, for despite Lady Selina’s anguished glances, and steady leading of the conversation to the Women’s Institute performance of Box and Cox, impending three weeks hence, her guests could not be induced to talk of anything but Lord Comstock’s death. He had never been invited to her table in life—not that he would have come, though he knew to a sixpence the news value of a marquess’s daughter; his notions of entertainment were quite other. Now, by reason of a small blue hole in his temple, he took possession of her mahogany, and lorded it over the excellent food, the candles, the tranquil roses. But this disregard of the hostess’s wishes was understandable considering that one of the guests was none other than Canon Prichard, the Vicar of Winborough, he whose car had been aspersed by the Assistant Commissioner as that which fled so guiltily down Lord Comstock’s drive.

“When the police inquired of me by telephone,” said the Canon, to an attentive audience, “naturally I assured them that the car had never left the garage. I was in London all day—a most difficult session; Bishops’ ideas nowadays are startingly modern in some matters. I walked to the station. I walked back from the station this evening. But when I went at seven-thirty into the garage, unlocking the door as usual—”

(“A padlock, Canon?” from Mrs. Bradley.

“Quite an ordinary padlock, yes.) I went in, I inspected the car, which looked much as usual. I did not examine the speedometer. But—and this is a very curious coincidence; quite providential, if one may use that word with reverence in connection with machinery. Just at the entrance to your drive, Lady Selina, by the lodge, my car coughed, and spluttered, and finally ceased to move.”

Exclamations from the rapt throng.

“You will guess, probably sooner than I did, the true cause. I examined the tank by the aid of a handy little pocket rule which I make it a practice to keep among my tools. Empty! The tank, which to my knowledge had held a gallon when I returned last night from a visit to Meauchamp, was empty.”

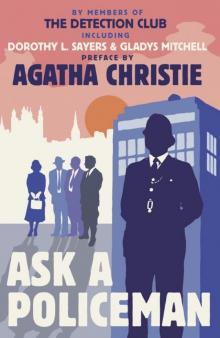

Ask a Policeman

Ask a Policeman